Cupressaceae

Fitzroya cupressoides

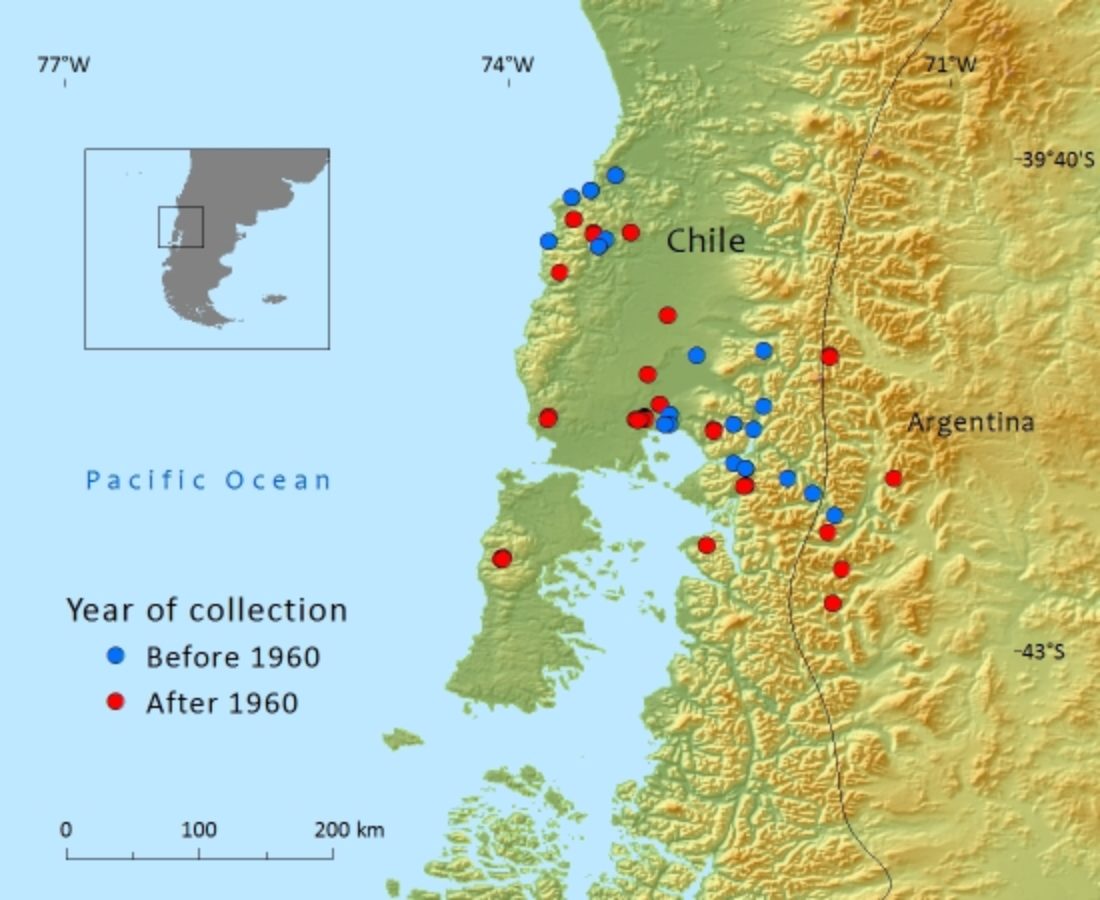

A genus with a single species endemic to Argentina and Chile where it is globally threatened by selective logging, grazing and fire

Description

Habit

Large evergreen tree to 50m, dioecious or rarely monoecious; pyramidal or sometimes stunted into low shrubs at high elevations. Trunk 2.5–5m in diameter; bark brownish red, deeply furrowed, fibrous.

Foliage

Leaves arranged in alternating whorls of three, rarely in twos or fours, deep green or glaucous, of two types: i) on mature branches 2.5–3mm long, scale-like, ovate, tightly imbricate, keeled and with a narrow decurrent base ii) on immature branches spathulate 5–8mm long, falcate and flattened. Stomata arranged in bands near the margin and keel, on both surfaces of the leaf.

Cones

Male pollen-cones terminal, solitary on short axillary branches, 6–8mm long, yellowish white.8mm long, yellowish white. Female seed-cones globose, 6–8mm, solitary, terminal on short lateral shoots, green at first, maturing brown with 6–8 woody scales in alternating whorls of 3, each scale with a prominent umbo. Seeds 2–3mm in diameter, each with 2–3 wings; maturing from February to March.

Key characters

Fitzroya could be confused with Pilgerodendron uviferum. In Fitzroya the leaves are usually arranged in alternating whorls and are of two types: scale-like and strongly keeled on mature branches, falcate and flattened on immature branches. All leaves have two obvious white stomatal bands on the underside. In Pilgerodendron the leaves are regularly arranged in decussate pairs, incurved, triangular and keeled on the back.

Human Uses

Despite national and international legal protection, particularly in Chile, its timber has continued to be exploited and this is reflected in the fact that during 1977–1996 the export value of alerce timber reached an average of US $865,000 (Díaz et al.,1997). Logging permits are issued for timber declared to originate from trees that died prior to 1976 when alerce was declared a National Monument and the cutting of live tres prohibited. Determining the date of death can be problematic and there have been many instances of fires being deliberately set in forests in the Chilean Andes and Coastal ranges in order to produce more dead timber for harvesting (Lara et al., 2003; Wolodarsky & Lara, 2005).

References and further reading

- Alnutt, T., Newton, A.C., Lara, A., Premoli, A., Armesto, J. & Gardner, M.F. (1999.) Genetic variation in Fiitzroya cupressoides (alerce), a threatened South American conifer. Journal of Melecular Ecology 8: 975–987.

- Benoit, C. & Ivan, L. (eds) (1989). Libro Rojo de la Flora Terrestre de Chile. Impresora Creces Ltd, Santiago.

- Benoit, C.I. (ed.). (1989). Red data book on Chilean terrestrial flora. (Part One). pp. 91. Chilean Forestry Service (CONAF), Santiago.

- Cόrtes, M.A. (1990). Estructura y dinámica de los bosques de Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides (Mol.) Johnston) en la Cordillera de la Costa de la Provincia de Valdivia. Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Austral de Chile.

- Corporaciόn Nacional Forestal (CONAF). (1985). Distribuciόn, Caracterisiticas, Potencialidad y Manejo de los Suelos bajo Alerce, Fitzroya cupressoides en la X Regiόn. Informe I. Boletín Técnico No. 18. Valdivia.

- Corporaciόn Nacional Forestal (CONAF). (1998). Informaciόn Estadí stica Histόrica de Ocurrencia y Daño de los Incendios Forestales: Perí odo 1978–1998. Décima Regiόn de los Lagos. Puerto Montt, Chile.

- Donoso, C. (1993). Producciόn de semillas y hojarasca de las especias de tipo forestal Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides) de la Cordillera de la Costa de Valdivia. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 66: 53–64.

- Donoso, C., Córtes, M. and Soto, L. (1980). Antecedentes sobre semillas y germinación de alerce, ciprés de las guaitecas, ciprés de la cordillera y tineo. Bosque 3: 96–100.

- Donoso, C., Cόrtes, M. & Escobar, B. (1993). Efecto del árbol semillero y la época de cosecha de semillas en la capacidad germinativa en vivero de Fitzroya cupressoides. Bosque 14: 63–71.

- Donoso, C., Sandoval, V., Grez, R. & Rodríguez, J. (1993). Dynamicas of Fitzroya cupressoides forest in southern Chile. Journal of Vegetation Science 4: 303–312.

- Díaz, S., Cuq, E. & Lara, A. (1997). Informe sobre Cortas ilegales y Exportaciόn de Alerce 1997. WWF/Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia.

- Fraver, S., González, M.E, Silla, F., Lara, A. & Gardner, M.F. (1999). Composition and structure of remnant Fitzroya cupressoides forests of Southern Chile's Central Depression. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 126(1): 49–57.

- Golte, W. (1996). Exploitation and conservation of Fitzroya cupressoides in southern Chile. In: D.R Hunt (ed.) Temperate Trees under Threat. Proceedings of an IDS Symposium on the Conservation Status of Temperate Trees, 30 Sept.–1 Oct. 1994.

- Hechenleitner, P., Gardner, M., Thomas, P., Echeverría, C., Escobar, B., Brownless, P. & Martínez, C. 2005. Plantas amenazadas del Centro-Sur de Chile. Distribución, Conservación y Propagación. Universidad Austral de Chile y Real Jardín Botánico de Edimburgo, , Santiago.

- Kitzberger T., Peréz A., Iglesias G., Premoli A. & Veblen T. (2000). Distribución y estado de conservación del alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides (Mol.) Johnst.) en Argentina. Bosque 2(1): 79–89.

- Lara A., Echeverría,C., Thiers, O.,Huss,E., Escobar, B., Tripp, K., Zamorano, C. & Altamirano, A. (2008). Restauración ecológica de coníferas longevas: el caso de Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides) en el sur de Chile. En: González-Espinosa, M., Rey-Benayas J. M., y Ramírez-Marcial, N. 2008. Restauración de bosques en América Latina. Fundación internacional para la restauración de ecosistemas (FIRE) y Ediciones Mundi-Prensa, pp. 39–56. Madrid, España.

- Lara, A. (1991). A Strategy for the Conservation of Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides) Forests in Chile. WWF.

- Lara, A. (1991). The dynamics and disturbance regimes of Fitzroya cupressoides forests in the south central Andes of Chile. PhD thesis. University of Colorado.

- Lara, A. & Villalba, R. (1993). A 3620-year temperature reconstruction from Fitzroya cupressides tree rings in southern South America. Science 260: 1104–1106.

- Lara, A., Gardner, M.F. & Vergara, R. (2003). The use and conservation of Fitzroya cupressoides (Alerce) Forests in Chile. In: R.R.Mill (ed.), The International Conifer Conference 1999 615: 381–385. Wye College, Kent, England.

- Lara, A., Villalba, R., Aravena, A., Wolodarsky, A. & Neira, E. (2000). Desarrollo de una red de cronologías de Fitzroya cupressoides (Alerce) para Chile y Argentina In: Roig, F. (ed.) Dendrocronolgia en América Latina. pp. 217–244. Ediciones Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina.

- Oldfield, S. (1983). Plants and CITES: Fitz-roya back in trade! Threatened Plants Newsletter 12(13).

- Parker, T. & Donoso, C. (1993). Natural regeneration of Fitzroya cupressoides in Chile and Argentina. Forest Ecology and Management 59(63-85): 63–85.

- Premoli A., Kitzberger T. & Veblen T. (2000). Conservation genetics of the endangered conifer Fitzroya cupressoides in Chile and Argentina. Conservation Genetics 1(1): 57–60.

- Premoli, A. Souto, C.P., Lara, A. & Donoso, C. (2003). Variacion en Fitzroya cupressoides (Mol.) Johnston (Alerce o Lahuán). In: Donoso, C., Premoli, A., Gallo, L. & IIpinza, R. (ed.), Varaciόn intraespecifica en las Especies arbόreus de los Bosques templados de Chile & Argentina, pp. 420. Editorial Universataria, Santiago.

- Premoli, A., Vegara, R., Souto, C.P., Lara, A. & Newton, A. (2003). Lowland valleys shelter the ancient conifer Fitzroya cupressoides in the Central Depression of southern Chile. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 33(3): 623–631.

- Premoli, A., Quiroga, P., Souto, C. & Gardner, M. (2013). Fitzroya cupressoides. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 06 July 2013.

- Veblen T. & Ashton D. (1982). The regeneration status of Fitzroya cupressoides in the Cordillera Pelada, Chile. Biological Conservation 23(2): 141–161.

- Veblen T., Delmastro R. & Schlatter J. (1976). The conservation of Fitzroya cupressoides and its environment in southern Chile. Environmental Conservation 3(4): 291–300.

- Veblen,T.T., Burns, B.R., Kitzberger, T., Lara, A. & Villalba, R. (1995). The Ecology of the Conifers of Southern South America. In: Enright, N.J. & Hills, R.S. (ed.), Ecology of the Southern Conifers, pp. 142–148. Melbourne University Press, Victoria.

- Wolodarsky-Franke, A. & A. Lara. (2005). The role of ‘‘forensic’’ dendrochronology in the conservation of alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides (Molina) Johnston) forests in Chile. Dendrochronologia 22: 235–240.