Cupressaceae

Chamaecyparis lawsoniana

Human Uses

Culturally Significant Products for American Indian Tribes. The current range of POC falls within the traditional territories of numerous American Indian Tribes along the west coast of North America. Included is the 5,400-acre forest of the Coquille Indian Tribe in west-central Oregon which is managed according to many of the Standards and Guidelines of adjacent Federal land. POC continues to play a significant role in the cultural and religious life of many Tribes living within the POC range from west-central Oregon south through northwest California. Specific information concerning where, how, what time of year, and by whom POC is harvested and used is restricted from distribution. Cedars of all types are considered the most used wood by native cultures of the Pacific Northwest. Despite declining availability, the cultural importance of POC remains high given its physical and structural characteristics, distinctive appearance, and aroma. The smells of POC also enhance the meaning of cultural rituals. Known for its durability, POC has straight grain properties allowing it to be split evenly. POC is sought as a source of planks for building traditional structures and for arrows or lances that support bone or stone projectile points. However, shortages and diminishing accessibility to mature trees sometimes relegates POC to parts of a plank house or sweat lodge, such as benches or sidewalls. This is also true for construction of canoes. POC has other traditional uses. Boughs are used as brooms, and the bark and roots are peeled and finely shredded for use in making traditional clothing, basketry, nets, twine, mats, and other items. Limbs may be twisted into rope. Unlike Western Red Cedar and Incense Cedar, POC has limited medicinal value due to its highly toxic character as a diuretic. Similarly, POC is less effective than Incense Cedar for preserving and storing perishable materials such as feathers, hides, and other materials. POC typically does not have the cedar-closet aroma of other cedars. The declining availability of healthy, mature POC trees through the 20th century has increased the importance of remaining POC stands to Tribes. Although the region has experienced an economic and cultural rejuvenation by the Tribes, a declining availability of POC due to several factors, including past timber cutting, disease, endangered species protection, fish protection, and land use allocations, hinders Tribal initiatives to restore and revive cultural traditions. Agencies issue permits for collection of special forest products including non-POC boughs, bear grass, and cones, but seldom issue permits for POC product collections. Therefore, quantitative data concerning modern-day cultural uses of POC is highly variable among the Tribes and generally not readily available outside Tribal communities. In general, however, use of POC is at modest levels. Maintenance of POC stands on Federal lands as a culturally-important species is important to Tribes and fulfils Federal policies and goals for accommodating traditional Tribal uses. These uses are also consistent with the “American Indian Religious Act,” and other statutes that highlight the importance of traditional cultural uses of plants on Federal lands. There are no effects to the exercise of those rights, because there are no off reservation treaty reserved rights within POC range.

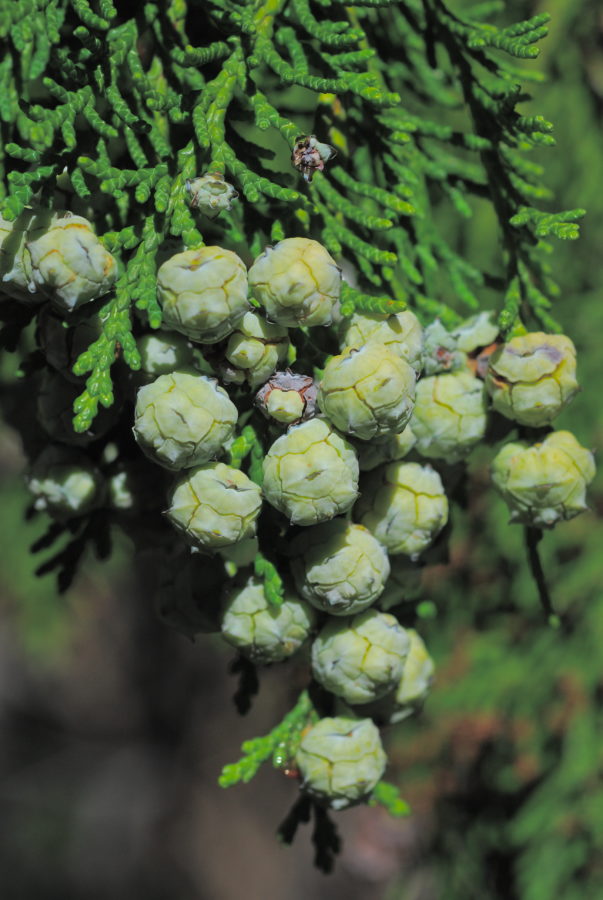

Special Forest Products POC shares the same decay-resistant properties as other cedars, such as Western Red Cedar and Incense Cedar, and is used for posts, rails, and shakes. Western Red Cedar and Incense Cedar are more sought after because they have a wider range and are more easily accessible. POC is in greatest demand for boughs during Christmas and to a lesser degree, for year-long floral arrangements. Boughs have a graceful, flat, beaded-lace appearance that makes them ideal for tying continuous strands to a wire backing for garlands or for layering into Christmas wreaths. The foliage also combines beauty with durability and needle retention that allows it to be preserved with glycerin mixtures for long-lasting floral displays. These attributes make POC a desirable commodity for personal use and commercial harvest. Commercial buying sheds in southwest Oregon purchased more than 400,000 pounds of POC boughs during 2002, yet less than four percent came from Federal land. The existing market for POC boughs could accommodate an increase in Federal bough supply either through expansion of demand or substituting POC boughs for western red cedar boughs. The price paid by the sheds ranged from $0.25 to $0.35 per pound, making POC economically desirable to harvest during a time of year when other agricultural work is diminishing.

Timber Harvest Timber harvest occurs for a variety of reasons on the BLM and FS units within the range of POC. An understanding of timber harvest activity and the lands involved is illustrative about the amount and nature of harvest activity on public lands, acknowledged to be a factor in POC root disease spread. Probable Sale Quantity Within the Oregon portion of the range of POC, long-term sustained-volume production is a Northwest Forest Plan goal on about 11 percent of the Federal forestlands. These lands which comprise the harvest landbase, the Matrix and Adaptive Management Area land allocations, are managed for regularly-scheduled timber harvest while meeting a non-declining yield policy objective. The annual timber harvest volume expected to come from these lands is called probable sale quantity, or PSQ. On most of the Federal land management units in Oregon, POC is concentrated within the riparian areas and therefore contributes little towards the PSQ. The exceptions to this are on the Coos Bay BLM lands and the Powers Ranger District of the Rogue River - Siskiyou NF. Within this area, POC is more well-distributed across the landscape resulting in about 5 percent of the volume in any given harvest unit being POC. Diseaserelated POC mortality does not necessarily affect attainment of the PSQ. In addition to generally being only a minor stand component, the dead trees remain salvageable for long periods of time, and their growing space, if not readily captured by existing competitors, will be naturally restocked with other tree species.

Harvest Activity. Annual volume of timber harvested on Federal lands in the Oregon portion of the POC range is about 49 million board feet (PSQ plus reserve thinning and salvage volume). This results in harvest on approximately 2,500 acres per year. With 20 percent of the range actually having POC, and 13 percent of that being infested with Phytophthora lateralis (PL), about 65 acres of harvest are likely to occur on PL-infested soils in any given year.

Timber Harvest on Private Lands within the Range of Port Orford Cedar. Silvicultural practices on private lands within the range of POC include commercial thinning and regeneration harvesting and their related treatments of burning, planting, spraying of herbicides, pre-commercial thinning, pruning, and fertilization. Recent declines in Federal harvests, economic conditions, and the increase in mills specializing in smaller material has led to shorter rotations and more regeneration harvesting. Rotation ages average 45 years on the coast, and 60 to 90 years in the interior. However, annual harvest of POC on private lands varies widely depending upon market conditions. The harvest levels shown in Table 3 are probably unusually high, based on a peak in demand that drove the price to a high of $12,000 per thousand board feet for top quality logs in the early 1990s as compared to $2,500 per thousand board feet today. Most POC harvested in California is transported to mills in Oregon or export facilities in Oregon or Washington. This amounts to about 840 truckloads from Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, based on 4.2 million board feet per year (Waddell and Bassett 1996). During Fiscal Year 2000 approximately 0.8 million board feet of POC was exported from the northwest to Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan from the ports of Longview, Coos Bay, Portland, and Seattle. There are no POC export ports in California; all POC harvested for export in California is shipped through Oregon. Recently, POC logs shipped from the Port of Coos Bay in Fiscal Year 2000 averaged 257 thousand board feet (Warren 2002). By 2002, this had dropped to 200 thousand board feet (Green 2003). Overall export trends for POC continue to decline as the overseas demand continues to drop due to economic conditions and the increased production of Hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa), which is used in Japanese temples. Several mills in Oregon saw about 4.5 million board feet of POC annually for lumber, panelling, and decking. These mills are located in Bandon, Glide, Myrtle Point, Riddle, and Roseburg. Since the overall export prices for POC have dropped, these mills have been able to purchase more POC. Sources of POC logs include both Oregon and northern California. Approximately 100 to 200 thousand board feet of California POC logs are shipped to Oregon mills annually representing 20 to 40 truckloads of logs. Mill production is limited by the supply of POC logs, as their product demand is strong. From 2000 to 2011, total harvest of POC on the Rogue River – Siskiyou National Forest was 293,000 board feet or between five and six log truck loads annually

References and further reading

- Betlejewski, F. 2009. Persistence of Phytophthora lateralis After Wildfire: Preliminary Monitoring Results From the 2002 Biscuit Fire. In: E.M. Goheen and S.J. Frankel (eds), Proceedings of the fourth meeting of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) Working Party S07.02.09 Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-221. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Albany, CA.

- IUCN. 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (ver. 2013.1). Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed: 12 June 2013).

- USDA. 2003. A Range-wide Assessment of Port-Orford-Cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) on Federal Lands. Unites States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service and Unites States Department of the Interior –Bureau of Land Management, Portland, OR.

- USDA. 2004. Final Environmental Impact Statement –Biscuit Fire Recovery Project, United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service and Unites States Department of the Interior –Bureau of Land Management, Medford, OR.

- USDA. 2004. Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – Management of Port-Orford-Cedar in Southwest Oregon. Unites States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service and Unites States Department of the Interior –Bureau of Land Management, Portland, OR.

- USDA. 2004. Record of Decision and Land and Resource Management Plan Amendment for Management of Port-Orford-Cedar in Southwest Oregon, Siskiyou National Forest. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, Portland, OR.

- USDA. 2006. Managing for Healthy Port-Orford-cedar in the Pacific Southwest Region. Unites States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region, Vallejo CA.

- USDA. 2010. Port-Orford-cedar Root Disease Resistance Breeding Program- Regions 5 and 6 Reforesting Burned Areas with Port-Orford-cedar Using Genetically Resistant Planting Stock in Post-Fire Reforestation Efforts. Unites States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service, Pacific Northwest and Pacific Southwest Regions, Vallejo CA.

- Zobel, D.B., Roth, L.F. and Hawk, G.M. 1985. Ecology, Pathology and Management of Port-Orford Cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana). General Technical Report PNW 184. Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA, Portland.