Cupressaceae

Sequoiadendron giganteum

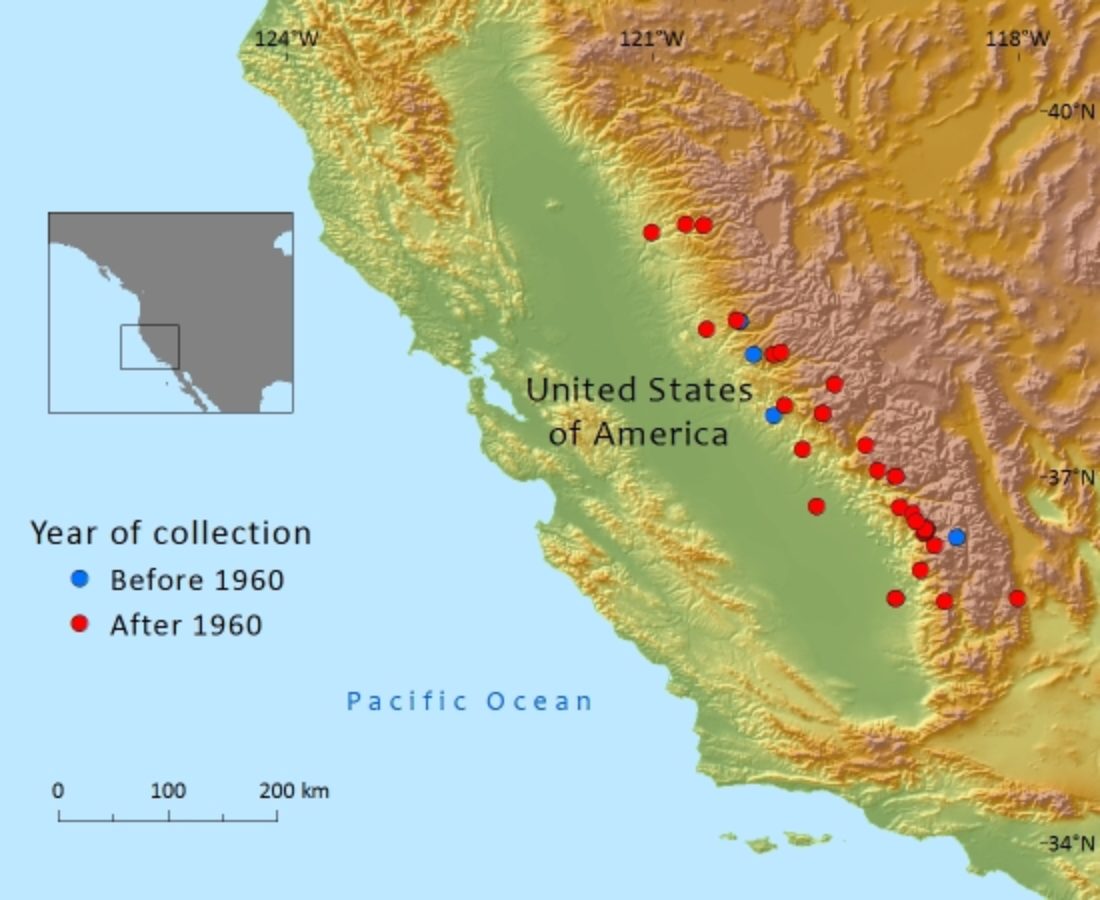

Restricted to California, USA where the groves have declined due to past logging. Today the main threats relate to fire management regimes, increases in the severity and frequency of fires and changes in precipitation patterns associated with drought.

Human Uses

Since its discovery by Europeans in the mid-19th century, exploitation during the latter half of that century and into the next was considerable. The trees, though of high lumber quality and rot-resistant, often shattered on impact after felling. What wood could be used was put into mainly building applications, and many larger houses in San Francisco and the Bay Area were built of its timber. No commercial exploitation of wild groves occurs at present, and most of these were protected for their scenic and scientific values many years ago. The giant trees are a major international tourist attraction in California. The Giant Sequoia is also highly regarded as an ornamental tree in parks and gardens of large homes and, being easily propagated from seed, is sold by many tree nurseries. Several cultivars have been named and are in the trade. The species also has potential as a managed-forest tree for timber production, but has found few applications in commercial forestry thus far.

References and further reading

- Aune, P.S. (1994). Proceedings of the symposium on Giant Sequoias: their place in the ecosystem and society, June 23-25, 1992. Gen. Tech. Report PSW-GTR-151. USDA Forest Service , Visalia, California.

- Brown, P.M., Hughes, M.K., Baisan, C.H., Swetnam, T.W. & A.C. Caprio (1992). Giant sequoia ring-width chronologies from the central Sierra Nevada, California. Tree-Ring Bulletin

- Burns, R.M. & Honkala, B.H. (1990). Silvics of North America. USDA, Forest Service, Washington, DC.

- Dodd, R.S., R. DeSilva (2016). Long-term demographic decline and late glacial divergence in a Californian paleoendemic: Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia). Ecology and Evolution 6(10):3342-3355.

- Douglass, A.E. (1945). Survey of sequoia studies. Tree-Ring Bulletin 11(4):26-32. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol11_4.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1945). Survey of sequoia studies, II. Tree-Ring Bulletin 12(2):10-16. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol11_4.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1946). Sequoia survey-III: Miscellaneous notes. Tree-Ring Bulletin 13(1):5-8. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol12_2.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1949). A superior sequoia ring record. Tree-Ring Bulletin 16(1):2-6. ( www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol16_1.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1950). A superior sequoia ring record. II. A.D. 870-1209. Tree-Ring Bulletin 16(3):24. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol16_3.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1950). A superior sequoia ring record. III. A.D. 360-886. Tree-Ring Bulletin 16(4):31-32. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol16_4.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Douglass, A.E. (1951). A superior sequoia ring record. IV. 7 B.C. - A.D. 372. Tree-Ring Bulletin 17(3):23-24.

- Douglass, A.E. (1951). A superior sequoia ring record. V. 271 B.C. - 1 B.C. Tree-Ring Bulletin 17(4):31-32. (www.treeringsociety.org/TRBTRR/TRBvol17_4.pdf, accessed 2006.06.05.)

- Elliott-Fisk, D. L., S. L. Stephens, J. E. Aubert, D. Murphy & J. Schaber. (1997). Mediated Settlement Agreement for Sequoia National Forest, Section B. Giant Sequoia Groves: an evaluation. Pp. 277-328 in SNEP Science Team and special consultants, Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress: status of the Sierra Nevada. Wildland Resources Center report, no. 40. Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California, Davis.

- Hartesveldt, R.J., H.T. Harvey, H.S. Shellhammer & R.E. Stecker. (1975). The Giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada. . U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

- McGraw, D.J. (2003). Andrew Ellicott Douglass and the giant sequoias in the founding of dendrochronology. Tree-Ring Research 59(1):21-27

- Schmid, R. & M. Schmid 2012. Sequoiadendron giganteum (Cupressaceae) at Lake Fulmor, Riverside County, California. Aliso 30(2):103-107.

- Schmid, R. & Farjon, A. (2013). Sequoiadendron giganteum. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 07 July 2013.

- Stephenson, N. L. (1996). Giant sequoia management issues: protection, restoration, and conservation. SNEP Science Team and special consultants, Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress: Status of the Sierra Nevada. Vol. 2. Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California, Davis

- Swetnam, T.W. (1993). Fire history and climate change in giant sequoia groves. Science 262: 885-889.

- Willard, D. (2000). A guide to the sequoia groves of California. Yosemite Association, Yosemite National Park.